Naqsh-e Jahan Square Built by Shah Abbas I the Great at the beginning of the 17th century, and bordered on all sides by monumental buildings linked by a series of two-storeyed arcades, the site is known for the Royal Mosque, the Mosque of Sheykh Lotfollah, the magnificent Portico of Qaysariyyeh and the 15th-century Timurid palace. They are an impressive testimony to the level of social and cultural life in Persia during the Safavid era.

Brief Synthesis of Naqsh-e Jahan square

The Naqsh-e Jahan Square is a public urban square in the center of Esfahan, a city located on the main north-south and east-west routes crossing central Iran. It is one of the largest city squares in the world and an outstanding example of Iranian and Islamic architecture. Built by the Safavid shah Abbas I in the early 17th century, the square is bordered by two-storey arcades and anchored on each side by four magnificent buildings: to the east, the Sheikh Lotfallah Mosque; to the west, the pavilion of Ali Qapu; to the north, the portico of Qayssariyeh; and to the south, the celebrated Royal Mosque. A homogeneous urban ensemble built according to a unique, coherent, and harmonious plan, the Naqsh-e Jahan Square was the heart of the Safavid capital and is an exceptional urban realization.

Meidan Emam is not typical of urban ensembles in Iran, where cities are usually tightly laid out without sizable open spaces. Esfahan’s public square, by contrast, is immense: 560 m long by 160 m wide, it covers almost 9 ha. All of the architectural elements that delineate the square, including its arcades of shops, are aesthetically remarkable, adorned with a profusion of enameled ceramic tiles and paintings.

Of particular interest is the Royal Mosque (Masjed-e Shah), located on the south side of the square and angled to face Mecca. It remains the most celebrated example of the colorful architecture which reached its high point in Iran under the Safavid dynasty (1501-1722; 1729-1736). The pavilion of Ali Qapu on the west side forms the monumental entrance to the palatial zone and to the royal gardens which extend behind it. Its apartments, high portal, and covered terrace (tâlâr) are renowned. The portico of Qeyssariyeh on the north side leads to the 2-km-long Esfahan Bazaar, and the Sheikh Lotfallah Mosque on the east side, built as a private mosque for the royal court, is today considered one of the masterpieces of Safavid architecture.

The Naqsh-e Jahan Square was at the heart of the Safavid capital’s culture, economy, religion, social power, government, and politics. Its vast sandy esplanade was used for celebrations, promenades, and public executions, for playing polo and for assembling troops. The arcades on all sides of the square housed hundreds of shops; above the portico to the large Qeyssariyeh bazaar a balcony accommodated musicians giving public concerts; the tâlâr of Ali Qapu was connected from behind to the throne room, where the shah occasionally received ambassadors. In short, the royal square of Isfahan was the preeminent monument of Persian socio-cultural life during the Safavid dynasty.

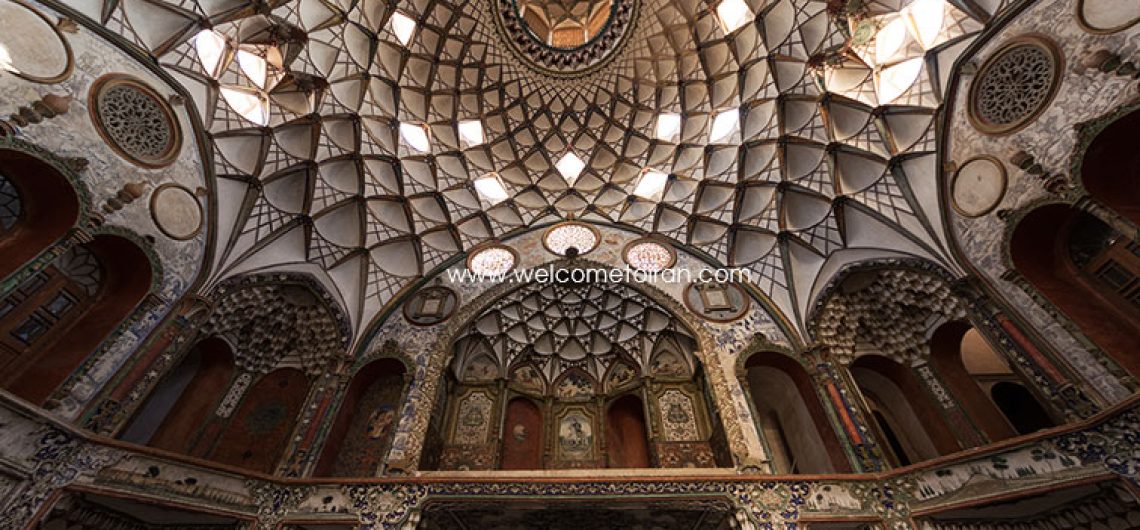

Criterion (i): The Naqsh-e Jahan Square constitutes a homogenous urban ensemble, built over a short time span according to a unique, coherent, and harmonious plan. All the monuments facing the square are aesthetically remarkable. Of particular interest is the Royal Mosque, which is connected to the south side of the square by means of an immense, deep entrance portal with angled corners and topped with a half-dome, covered on its interior with enameled faience mosaics. This portal, framed by two minarets, is extended to the south by a formal gateway hall (iwan) that leads at an angle to the courtyard, thereby connecting the mosque, which in keeping with tradition is oriented northeast/southwest (towards Mecca), to the square’s ensemble, which is oriented north/south.

The Royal Mosque of Esfahan remains the most famous example of the colorful architecture which reached its high point in Iran under the Safavid dynasty. The pavilion of Ali Qapu forms the monumental entrance to the palatial zone and to the royal gardens which extend behind it. Its apartments, completely decorated with paintings and largely open to the outside, are renowned. On the square is its high portal (48 meters) flanked by several storeys of rooms and surmounted by a terrace (tâlâr) shaded by a practical roof resting on 18 thin wooden columns.

All of the architectural elements of the Meidan Imam, including the arcades, are adorned with a profusion of enameled ceramic tiles and with paintings, where floral ornamentation is dominant – flowering trees, vases, bouquets, etc. – without prejudice to the figurative compositions in the style of Riza-i Abbasi, who was head of the school of painting at Esfahan during the reign of Shah Abbas and was celebrated both inside and outside Persia.

Criterion (ii): The royal square of Esfahan is an exceptional urban realization in Iran, where cities are usually tightly laid out without open spaces, except for the courtyards of the caravanserais (roadside inns). This is an example of a form of urban architecture that is inherently vulnerable.

Criterion (iii): The Meidan Imam was the heart of the Safavid capital. Its vast sandy esplanade was used for promenades, for assembling troops, for playing polo, for celebrations, and for public executions. The arcades on all sides housed shops; above the portico to the large Qeyssariyeh bazaar a balcony accommodated musicians giving public concerts; the tâlâr of Ali Qapu was connected from behind to the throne room, where the shah occasionally received ambassadors. In short, the royal square of Esfahan was the preeminent monument of Persian socio-cultural life during the Safavid dynasty (1501-1722; 1729-1736).

Integrity of Naqsh-e Jahan square

Within the boundaries of the property are located all the elements and components necessary to express the Outstanding Universal Value of the property, including, among others, the public urban square and the two-storey arcades that delineate it, the Sheikh Lotfallah Mosque, the pavilion of Ali Qapu, the portico of Qeyssariyeh, and the Royal Mosque.

Threats to the integrity of the property include economic development, which is giving rise to pressures to allow the construction of multi-storey commercial and parking buildings in the historic center within the buffer zone; road widening schemes, which threaten the boundaries of the property; the increasing number of tourists; and fire.

Authenticity of Naqsh-e Jahan square

The historical monuments at Meidan Emam, Esfahan, are authentic in terms of their forms and design, materials and substance, locations and setting, and spirit. The surface of the public urban square, once covered with sand, is now paved with stone. A pond was placed at the centre of the square, lawns were installed in the 1990s, and two entrances were added to the northeastern and western ranges of the square. These and future renovations, undertaken by Cultural Heritage experts, nonetheless employ domestic knowledge and technology in the direction of maintaining the authenticity of the property.

Management and Protection requirements

Meidan Emam, Esfahan, which is public property, was registered in the national list of Iranian monuments as item no. 102 on 5 January 1932, in accordance with the National Heritage Protection Law (1930, updated 1998) and the Iranian Law on the Conservation of National Monuments (1982). Also registered individually are the Royal Mosque (Masjed-e Shah) (no. 107), Sheikh Lotfallah Mosque (no. 105), Ali Qapu pavilion (no. 104), and Qeyssariyeh portico (no. 103). The inscribed World Heritage property, which is owned by the Government of Iran, and its buffer zone are administered and supervised by the Iranian Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism Organization (which is administered and funded by the Government of Iran), through its Esfahan office. The square enclosure belongs to the municipality; the bazaars around the square and the shops in the square’s environs are owned by the Endowments Office. There is a comprehensive municipal plan, but no Management Plan for the property. Financial resources (which are recognized as being inadequate) are provided through national, provincial, and municipal budgets and private individuals.

Sustaining the Outstanding Universal Value of the property over time will require developing, approving, and implementing a Management Plan for the property, in consultation with all stakeholders, that defines a strategic vision for the property and its buffer zone, considers infrastructure needs, and sets out a process to assess and control major development projects, with the objective of ensuring that the property does not suffer from adverse effects of development.

Reference: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/115