The majority of churches in Iran that possess historical and artistic value were built around the eight century A.H. or the 14th century AD, and the period thereafter. Of course, this does not mean that there were no churches existing in the country before that period.

During the reign of Shah Abbas, the Safavid king, his sagacious policies caused a sizable number of Armenians from Armenia and Azarbaijan to transfer and settle in Esfahan and other regions of Iran. A place called Jolfa was built on the banks of the Zayande-rud River in Esfahan and became the residence of these migrating people. Consequently, churches were erected in that town. Meanwhile, after a short lapse of time, some Armenians moved to Gilan and some resided in Shiraz.

After the death of Shah Abbas the First, his successor, Shah Abbas the Second, also paid close attention to the welfare of Armenians and more churches were erected in Jolfa. The influx of many Europeans during the reign of the Qajars led to the flourishing of other churches, in addition to those that were constructed previously. A number of these edifices have lasted and acquired architectural and artistic significance.

Azarbaijan is host to the oldest churches in Iran. Among the most significant are the Tatavous Vank (St. Tatavous Cathedral), which is also called the Ghara Kelissa (the black monastery). This is located at the Siahcheshmeh (Ghara-Eini) border area south of Makou. There is also the church known as Saint Stepanous, which stands 24 kilometers south of Azarbaijan’s Jolfa town.

Generally, each church has a large hall for congregational prayers; its foremost part is raised like a dais, adorned with the pictures or images of religious figures and it also serves as an altar. Here, candles are lit and the church mass is conducted by the priest. In the foreground is the praying congregation which faces the platform where the priest is leading the rites in the church; this is similar to the Muslim practice of praying facing the niche in the mosque. While the mass is being said, the people stand, kneel, or sit depending on what the rites require. The structure of churches in Iran follows more or less the pattern of Iranian architecture, or they are a mixture of Iranian and non-Iranian designs.

Churches in Iran

This is one of the old churches in Iran located at an intersection west of the Marand-Jolfa highway and east of the Khoy-Jolfa road. Also having a pyramidal dome, it is, nevertheless, quite beautiful and far more pleasant to behold than the Saint Tatavous church.

The general structure mostly resembles Armenian and Georgian architecture and the inside of the building is adorned with beautiful paintings by Honatanian, a renowned Armenian artist. Hayk Ajimian, an Armenian scholar and historian, recorded that the church was originally built in the ninth century AD, but repeated earthquakes in Azarbaijan completely eroded the previous structure. The church was rebuilt during the rule of Shah Abbas the Second.

Saint Mary’s Church in Tabriz

This church was built in the sixth century A.H. (12th century AD) and in his travel chronicles, Marco Polo, the famous Venetian traveler who lived during the eight century A.H. (14th century AD), referred to this church on his way to China. For so many years, Saint Mary’s served as the seat of the Azarbaijan Armenian Archbishop. It is a handsomely built edifice, with different annex buildings sprawled on a large area. A board of Armenian peers is governing the well- attended church.

Aside from the above three churches, there are others in Azarbaijan such as the old church built in the eight century A.H. at Modjanbar village, which is some 50 kilometers from Tabriz. Another one is the large Saint Sarkis church, situated in Khoy; this building has survived from the time of Shah Abbas the Second (12th century A.H.). During the reign of the said Safavid king, another edifice called the Saint Gevorg (Saint George) church was constructed, using marble stones and designed with a large dome, at Haft Van village near Shapur (Salmas). A church, also with a huge dome, likewise stands at Derishk village in the vicinity of Shapur, in Azarbaijan.

The Saint Tatavous Monastery or the Ghara Kelissa

Initially, this church in Iran comprised of a small hall with a pyramid- shaped dome on the top and 12 crevices similar to the Islamic dome-shaped buildings from the Mongol era. The difference was that the church dome was made of stone. The main part of this pyramid structure followed Byzantine (Eastern Roman) architecture, including the horizontal and parallel fringes made of white and black stones in the interior and black stones on the exterior facing.

Since the facade is dominated by black stones, the church was formerly called the Ghara Kelissa (or black monastery) by the natives. During the reign of the Qajar ruler, Fathalishah, new structures were added to the Saint Tatavous church upon the order of Abbas Mirza, the crown prince, and the governor of Azarbaijan. The renovations resulted in the enlargement of the prayer hall and the small old church was converted into a prayer platform, holding the altar, the holy ornaments and a place where the priest could lead the prayers.

The bell tower and the church entrance were situated at one side of the new building, but unfortunately, this part remained unfinished.

Meanwhile, due to border skirmishes and other political disturbances in the area during the succeeding periods, the church was abandoned and ruined. Some minor repairs have been carried out in recent years.

Each year, during a special season (in the summer), many Armenians from all parts of Iran travel to this site for prayer and pilgrimage. They come by jeeps or trucks after crossing a very rough mountainous passage.

They flock around the church, stay for a few days and perform their religions ceremonies. For the rest of the year, however, the church remains deserted in that remote area.

The additions made to the Saint Tatavous church on the order of Abbas Mirza consist of embossed images of the apostles on the facade and decorations of flowers, bushes, lion and sun figures and arabesques, all of which had been done by Iranian craftsmen. The architecture of the church interior is a combination of Byzantine, Armenian and Georgian designs. Beside the large church, special chambers have been built in the yard to shelter pilgrims and hermits.

Historical Churches at Jolfa of Esfahan

The most important historical church in Iran is the old cathedral, commonly referred to as the Vank (which means “cathedral” in the Armenian language). This large building was constructed during the reign of Shah Abbas the First and completely reflects Iranian architecture. It has a double-layer brick dome that is very much similar to those built by the Safavids. The interior of the church is decorated with glorious and beautiful paintings and miniature works that represent biblical traditions and the image of angels and apostles, all of which have been executed in a mixture of Iranian and Italian styles. The ceiling and walls are coated with tiles from the Safavid epoch.

At a corner of the large courtyard of the cathedral, offices and halls have been built to accommodate guests, the Esfahan archbishop and his retinue, as well as other important Armenian religious hierarchy in Iran. The church compound also includes a museum that is located in a separate building. The museum displays preserved historical records and relics, and the edicts of Iranian kings dating back to the time of Shah Abbas the First. It also contains an interesting collection of art work.

Esfahan has other historical churches, the most important of which is the Church of Beit-ol Lahm (Bethlehem) at Nazar Avenue. There are also the Saint Mary church at Jolfa Square and the Yerevan church in the Yerevan area.

The Armenian Church in Shiraz

In the eastern section of Ghaani Avenue, in a district called “Sare Jouye Aramaneh”, an interesting building has survived from the era of Shah Abbas the Second. Its principal structure stands in the midst of a gardenlike compound and consists of a prayer hall with a lofty flat ceiling and several cells flanking the two side of the building. The ceiling is decorated with original paintings from the Safavid era and the adjoining cells are adorned with niches and arches and plaster molding, also in the Safavid style. This is considered a historical monument at Shiraz and definitely worth a visit.

Saint Simon’s Church in Shiraz

This is another relatively important, but not so old church in Shiraz. The large hall is completely done in Iranian style while the roof is Roman. Small barrel-shaped vaults, many Iranian art work and stained-glass window panes adorn the church. Meanwhile, another church called the Glory of Christ, stands at Ghalat, 34 kilometers from Shiraz. This building has survived from the Qajar period and is surrounded by charming gardens.

Saint Tatavous Church, Tehran

This edifice is located at the Chaleh Meidan district, one of the oldest districts in Tehran. It stands south of the Seyed Esmail Mausoleum, at the beginning of the northern part of the so-called Armenians’ Street. The oldest church of Tehran, it was built during the reign of the Qajar king, Fathalishah. The building has a dome-shaped roof and four alcoves, an altar and a special chair reserved for the Armenian religions leader or prelate. The vestibule leading to the church contains the graves of prominent non-Iranian Christians who have died in Iran, and in the middle of the churchyard, Gribaydof, the Czarist ambassador at the court of Fathalishah, and his companions were laid to rest. They were killed by the revolutionary forces of Tehran at that time.

Meanwhile in Bushehr, there is a church from the Qajar period that is a good specimen of Iranian architecture. All the windows are modeled after old Iranian buildings and the colored panes are purely Iranian art work.

There are also many other churches in Iran such as Ourumieh, in hamlets surrounding Arasbaran, Ardabil, Maragheh, Naqadeh, Qazvin, Hameadan, Khuzestan, Chaharmahal, Arak, in the old Vanak village north of Tehran, etc. These churches, though, are all deserted and are of little artistic significance.

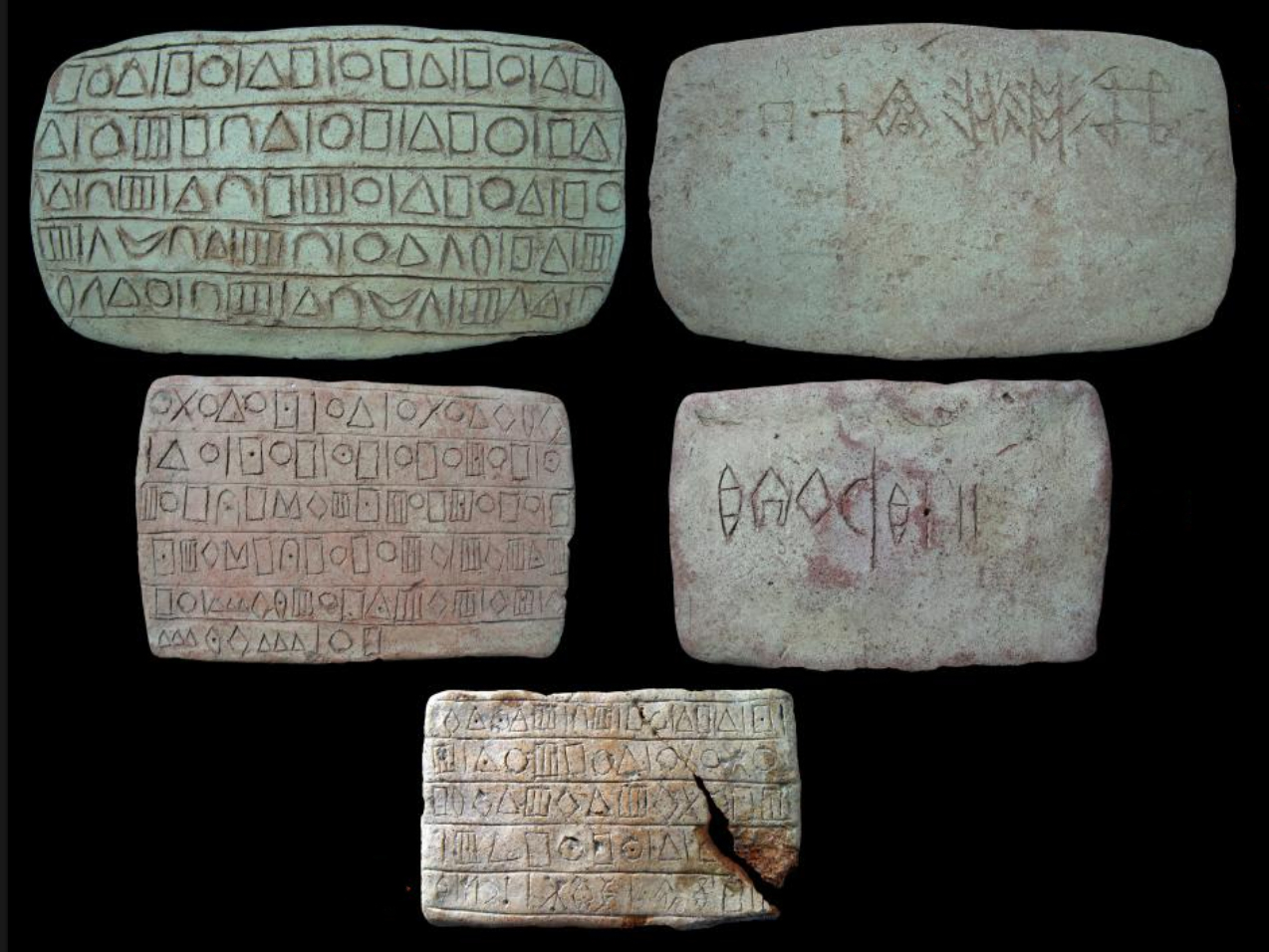

Konar Sandal Site & Mounds Near Jiroft

Konar Sandal Site & Mounds Near Jiroft

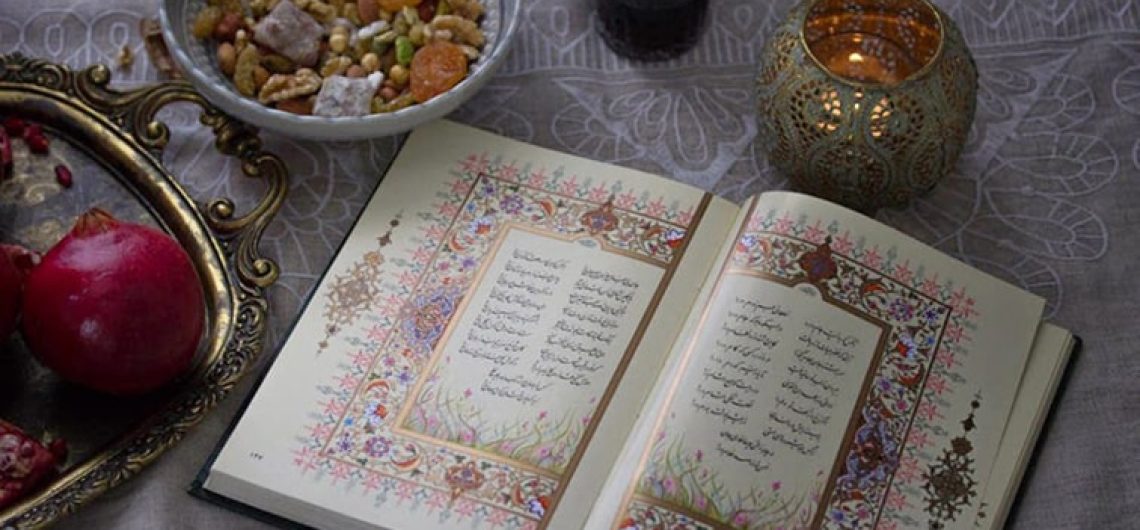

The Celebration of Nowruz

The Celebration of Nowruz