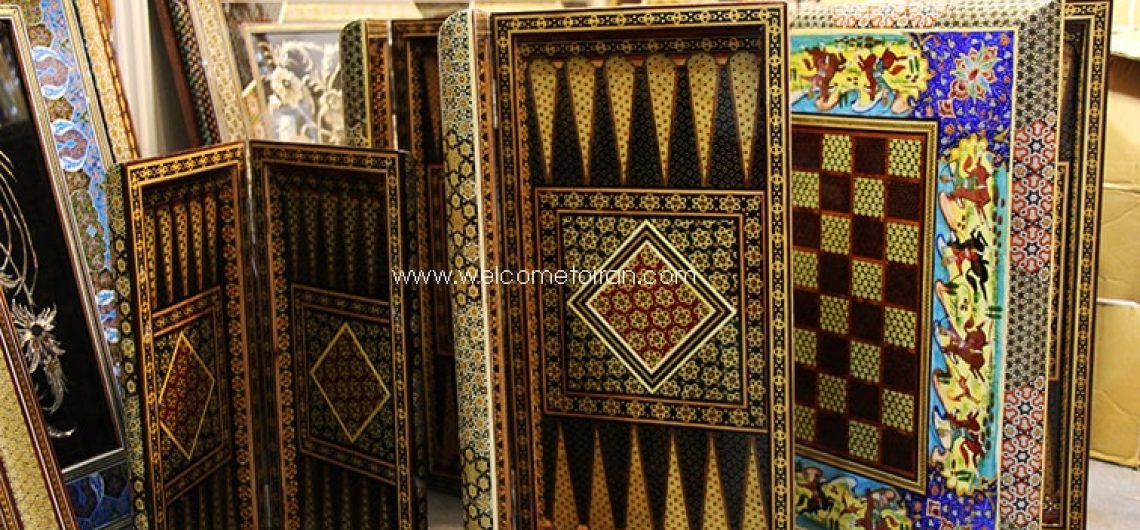

The creation of Persian tiles began about 1200 A.D. and Persian tiles decorating reached it’s zenith in the 18th and 19th centuries. On any tour for first time visitors, there are the “musts,” of course: the ancient ruins at Persepolis, the gardens in Shiraz, the palaces and mosques in Isfahan, the Crown Jewels in Tehran. But in just about every setting, artistry hides in plain sight: in carpets, calligraphy, pottery, miniatures, and the favorite one: Iranian tiles, which are dizzyingly, deliriously magical.

Simply put, Iran has the most beautiful tile work in the world. Over the centuries, glazed bricks and tiles have been used to decorate palaces, mosques, monuments, mausoleums, official buildings, schools, and shops.

The impact of Persian tiles occupies a prominent place in the history of Islamic art. Recognized for having one of the richest and varied art legacies, Persia (now Iran) used this form of art to decorate palaces, public buildings, monuments, mausoleums, and religious buildings, such as mosques and theological schools.

The importance of tile-work in Persian architecture arises from two important factors; first the need to weatherproof the simple clay bricks used in construction, and secondly the need to ornament the buildings. Tiles were used to decorate monuments from early ages in Iran. Everywhere you go in Iran you will see glistening, multi-colored tiles, coating the walls, domes and minarets of mosques, and decorating the edges of every kind of building from schools to government offices. The tiled domes of Iranian mosques, reminiscent of Faberge eggs in the vividness of their coloring, are likely to remain one of your abiding memories of Iran.

The earliest evidence of glazed brick is the discovery of glazed bricks in the Elamite Temple at Choqa Zanbil, dated to the 13th century BC. Glazed and colored bricks were used to make low reliefs in Ancient Mesopotamia, most famously the Ishtar Gate of Babylon (ca. 575 BC), now partly reconstructed in Berlin, with sections elsewhere. Mesopotamian craftsmen were imported for the palaces of the Persian Empire such as Persepolis.

The Achaemenid Empire decorated buildings with glazed brick tiles, including Darius the Great’s palace at Susa, and buildings at Persepolis.

The succeeding Sassanid Empire used tiles patterned with geometric designs, flowers, plants, birds and human beings, glazed up to a centimeter thick. Early Islamic mosaics in Iran consist mainly of geometric decorations in mosques and mausoleums, made of glazed brick. Typical turquoise tiling becomes popular in 10th-11th century and is used mostly for Kufic inscriptions on mosque walls. Seyyed Mosque in Isfahan (AD 1122), Dome of Maraqeh (AD 1147) and the Jame Mosque of Gonabad (1212 AD) are among the finest examples. The dome of Jame’ Atiq Mosque of Qazvin is also dated to this period.

A most famous example of early tile art on wares is the mosaic rhyton discovered in the excavations at Marlik. This vessel has two shells. The outer shell is covered with colored pieces of stone. This object is known as “Thousand Flowers”. This art has been improved in the Achaemenid, Parthian and Sassanid periods.

During the Safavid period, mosaic ornaments were often replaced by a haft rang (seven colors) technique. Pictures were painted on plain rectangle tiles, glazed and fired afterwards. Besides economic reasons, the seven colors method gave more freedom to artists and was less time-consuming. It was popular until the Qajar period, when the palette of colors was extended by yellow and orange. The seven colors of Haft Rang tiles were usually black, white, ultramarine, turquoise, red, yellow and fawn.

The Persianate tradition continued and spread to much of the Islamic world. Palaces, public buildings, mosques and tomb mausoleums were heavily decorated with large brightly colored patterns, typically with floral motifs, and friezes of astonishing complexity, including floral motifs and calligraphy as well as geometric patterns.

The golden age of Persian tilework began during the reign the Timurid Empire. In the mora technique, single-color tiles were cut into small geometric pieces and assembled by pouring liquid plaster between them. After hardening, these panels were assembled on the walls of buildings. But the mosaic was not limited to flat areas. Tiles were used to cover both the interior and exterior surfaces of domes. Prominent Timurid examples of this technique include the Jame Mosque of Yazd (AD 1324-1365), Goharshad Mosque (AD 1418), the Madrassa of Khan in Shiraz (AD 1615), and the Molana Mosque (AD 1444)

Other important tile techniques of this time include girih tiles, with their characteristic white girih, or straps.

Mihrabs, being the focal points of mosques, were usually the places where most sophisticated Persian tiles was placed. The 14th-century mihrab at Madrasa Imami in Isfahan is an outstanding example of aesthetic union between the Islamic calligrapher’s art and abstract ornament. The pointed arch, framing the mihrab’s niche, bears an inscription in Kufic script used in 9th-century Qur’an.

One of the best known architectural masterpieces of Iran is the Shah Mosque in Isfahan, from the 17th century. Its dome is a prime example of tile mosaic and its winter praying hall houses one of the finest ensembles of cuerda seca tiles in the world. A wide variety of tiles had to be manufactured in order to cover complex forms of the hall with consistent mosaic patterns. The result was a technological triumph as well as a dazzling display of abstract ornament.

The Celebration of Nowruz

The Celebration of Nowruz